Though the world is an increasingly small place, especially with electronic communication, it is always fun to discover connections between different parts of one’s life the old-fashioned way: through observation. The idea of this blog post developed while visiting family in my hometown of Beverly, Massachusetts this summer. I hope you will take the time to read it and enjoy the photographs.

I had the great privilege of attending Groton School, a boarding school in Groton Massachusetts. Though founded relatively recently (in 1884) history and tradition are central to its ethos. As an organ student, I spent many hours in the St. John’s Chapel, designed by Henry Vaughan and donated by one of the three founders of the school, William Amory Gardner, in memory of his brother Joseph Peabody Gardner.

In a letter dated Christmas Eve 1898, Gardner offered the Rector up to $75,000 to build a new chapel, with three stipulations:

“1. That the present Chapel be not disposed of without my advice and consent.

2. That the architect be chosen not without my consent.

3. That I have negative control over the location of windows, brasses, etc., kind of pews, etc.”

(The Trustees of Groton School, St. John’s Chapel, 1900-2000, (privately printed 2001), p. 9.)

Henry Vaughan was one of the architects suggested by Gardner. It is likely that he would have appealed to the low-church Headmaster Endicott Peabody and the school trustees because he had already designed the St. Paul’s School chapel in 1888 as well as the first Groton School chapel, which was moved into town (presumably at the suggestion of Gardner- see No. 1 above) to become Sacred Heart Roman Catholic Church. Vaughan must have appealed to the high-church Gardner because of his connection to Church of the Advent in Boston, where Vaughan was also a parishioner as was Gardner’s Aunt Isabella Stewart Gardner, and his fluency in historic Gothic Revival architecture. The decision was made (perhaps after some lobbying by Gardner) to employ Indiana limestone in the late 14-century English Gothic style, in the transitional period between Decorated and Perpendicular. (The Trustees of Groton School, St. John’s Chapel, 1900-2000, (privately printed 2001), p. 12.)

Gardner and two his brothers had been raised by Isabella Stewart Gardner after the death of his parents (his mother when he was 2 and his father when he was 12). Aunt Isabella, in later years, lived with a fabulous art collection in her own Venetian Palazzo, which she had purchased in its entirety, shipped to Boston, and rebuilt. Now the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, it is a must-see when visiting Boston. It was completed in 1903, three years after the chapel at Groton was consecrated. Though the three brothers were not raised in the Palazzo, it is still difficult to imagine the atmosphere in which they must have been raised. Hilliard T. Goldfarb, gives us a glimpse:

“In 1879, they took the three boys on an educational tour of French and English cathedrals, lightened by attendance at the Ascot races and at Oxford-Cambridge cricket matches. In London they studied the art collections and visited their countryman Henry James. It was during this visit that James introduced Isabella Gardner to James McNeill Whistler at a party given by Lady Blanch Lindsay.” (Hilliard T. Goldfarb The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum: A Companion Guide and History (Yale University Press, 1995) p.8)

When a student at Groton, I had also been intrigued by the “Gardner Room,” a faculty study lined with dark wood shelves full of old books, and exotic antique furniture that had belonged to Gardner. My attraction was of course intensified because students were not allowed in the room! Only later did I learn more about the man buried in the basement of the chapel (yes, there is a very simple tomb down there), including the fact that he had a summer estate in, of all places, my home town. I discovered the connection to Beverly when visiting my father at work one day. For many years he has worked at Endicott College and has had an office in “College Hall,” a large stone house. One day I looked carefully at the fireplace in the dining room and saw the Groton School crest on one side, the Harvard crest on the other (Gardner was a Harvard graduate), and what was presumably the family crest in the center.

The Gardner family had roots in adjacent Salem, Massachusetts prior to settling in Boston. This section of Beverly, called Pride’s Crossing, became a fashionable place for high-society summer homes. The campus of Endicott College contains no fewer than eight re-purposed historic houses. Down the street from the Gardner property was Henry Clay Frick’s summer estate Eagle Rock, since demolished. Gardner and his two brothers inherited land from their father. After the death of his brother Joseph, William Amory Gardner bought out his other brother and had “Stone House” designed by architect Henry Richards. It was built in 1915-1917 as his summer home, his main residence being on the Groton campus. After Gardner, a life-long bachelor, died in 1930, the building was vacant until the fledgling Endicott College, a junior college for women, leased and then purchased the building in 1939-1940.

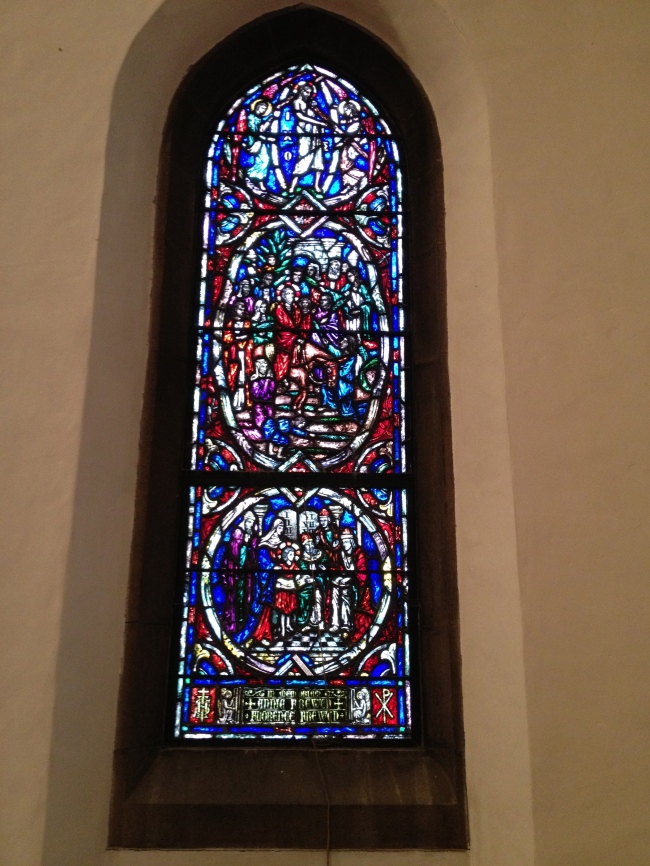

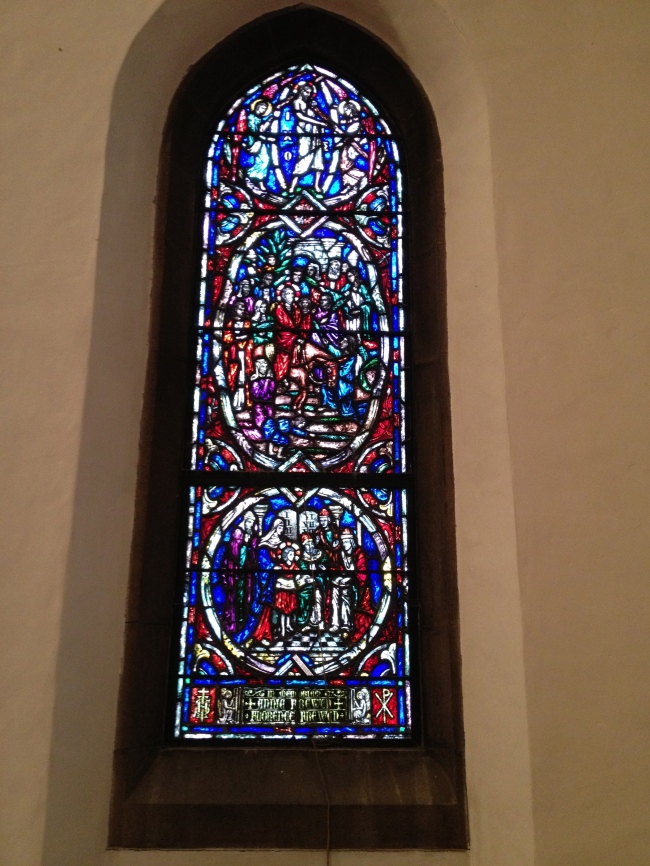

Having known this history for a number of years, I learned of yet another interesting connection on my trip this summer. I visited St. Peter’s Church in downtown Beverly and discovered that the choir stalls had been given in memory of William Amory Gardner. This surprised me, as I had assumed that he would have attended St. John’s Church in Beverly Farms, which was closer to his summer house and designed by Henry Vaughan in 1902, shortly after the Groton Chapel. Perhaps his family had older connections to St. Peter’s, or perhaps he just liked the church or the Rector better. St. Peter’s is a lovely little parish church that happens to contain some very fine stained-glass windows.

The windows in the chancel were designed and executed by Margaret Redmond, a pupil of Charles Connick (creator of many amazing windows throughout the country and the world). I will save a detailed discussion of American stained glass for another blog post. Though they were installed after Gardner’s death, I am quite sure that he would have approved.